MONTREAL - Louise Harel cried only once during the 1995 Quebec referendum.┬Ā

It was in the middle of the campaign, when she saw internal polling that showed the sovereigntists in the lead. Then a Parti Qu├®b├®cois minister, Harel said the numbers made her believe, for the first time, that Quebec might choose independence.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It was possible, it was achievable, and it was certainly the dearest wish I had in my life,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£I cried because we were winning. I never cried because we lost.ŌĆØ

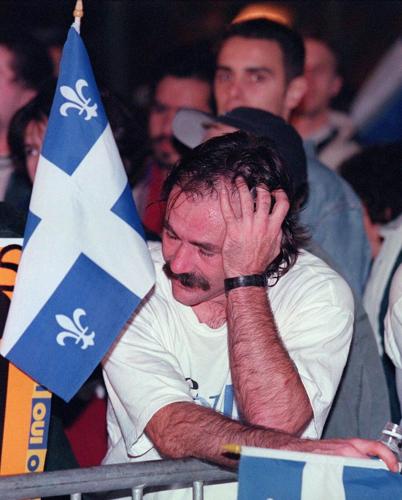

Thirty years after the 1995 referendum, when Quebecers came within a hairŌĆÖs breadth of voting to leave Canada, those who lived through it still remember the emotion of that time. They recall the drama of an unpredictable campaign, the fears and frustrations, and the relief ŌĆö or anguish ŌĆö when it was all over.┬Ā

One of the people watching the results on Oct. 30 that year was an 18-year-old college student, just old enough to have voted ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ to separation. He was at a friendŌĆÖs house with about 30 other students, dressed in a blue shirt bearing the fleur de lys.┬Ā

ŌĆ£We felt like we were about to witness a historic moment,ŌĆØ said Paul St-Pierre Plamondon in a recent interview. ŌĆ£And later that evening, we felt like a historic moment had slipped through our fingers.ŌĆØ

St-Pierre Plamondon, now the 48-year-old leader of the Parti Qu├®b├®cois, has promised a third referendum after the unsuccessful campaigns of 1980 and 1995 if his party forms government next year. With the PQ leading in the polls, he has pledged to reinvigorate a sovereigntist movement that has waxed and waned over the last 30 years.┬Ā

But looking back on the day after the vote in 1995, the crushing disappointment seems most vivid. ŌĆ£There was a heavy atmosphere,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£A deafening silence.ŌĆØ

It was clear from the start that the 1995 campaign was going to be different from 1980, when nearly 60 per cent of voters had rejected sovereignty in the province's first referendum, according to John Parisella, an adviser on the federalist campaign. That initial defeat prompted Parti Qu├®b├®cois founder Ren├® L├®vesque's famous words: ŌĆ£Until next time."

Back then, prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau promised constitutional change if Quebec voted to stay in Canada. But that promise did not bear fruit in Quebec, which never signed the 1982 Constitution Act. The subsequent failures of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords in 1987 and 1992 ŌĆö both attempts to bring Quebec into the constitutional fold ŌĆö helped renew support for sovereignty in the province.┬Ā

In September 1994, the Parti Qu├®b├®cois returned to power under premier Jacques Parizeau, who promised to hold a second referendum within a year. This time, Parisella said, the federal government of Liberal prime minister Jean Chr├®tien had little appetite for more promises of constitutional reform.┬Ā

ŌĆ£We entered the 1980 referendum with the hope that a vote for the ŌĆśnoŌĆÖ would be a vote for change,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£The optimism and the hope and the confidence in 1980 was not the same in 1995.ŌĆØ

Still, there was no obvious reason for federalists, led by Quebec Liberal leader Daniel Johnson, to panic after ParizeauŌĆÖs election. Minutes from Quebec cabinet meetings in early 1995 show that the premier and his ministers were worried about stagnating support for independence. One minister said in February he was ŌĆ£struck by the gloomy mood that has spread among our ranks.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£We were of the feeling that Quebecers did not want to leave Canada," Parisella said.┬Ā

In June, Parizeau signed a pact with Bloc Qu├®b├®cois leader Lucien Bouchard and Action d├®mocratique du Qu├®bec leader Mario Dumont, which promised that the referendum question would include a plan to seek a partnership with the rest of Canada. The deal was a compromise for the Quebec premier, who preferred a hard-line approach to separation, but it was a turning point that broadened the sovereigntist coalition, said Louise Beaudoin, one of ParizeauŌĆÖs ministers.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It really set a new tone and opened up all kinds of possibilities,ŌĆØ she said.┬Ā

But as the official campaign began in early October, the federalist camp maintained its lead in the polls. Chr├®tien, who was not popular in Quebec, was largely kept on the sidelines.┬Ā

Minutes from federal cabinet meetings, obtained using access-to-information law, show the prime minister was in contact with provincial premiers, who had agreed to work with Ottawa to defend national unity. But at the start of the campaign, the premiers were to keep their involvement "low key for the time being," according to the minutes. Chr├®tien expressed confidence in the "no" campaign.┬Ā

Meanwhile in Quebec, Beaudoin was meeting undecided voters on their doorsteps who told her theyŌĆÖd feel reassured by the "yes" campaign if only Bouchard, a charismatic leader and fiery orator, were more visible.┬Ā

Under pressure, Parizeau made what Beaudoin called an ŌĆ£extremely nobleŌĆØ decision. On Thanksgiving weekend, he named Bouchard the chief negotiator for partnership talks following a vote for independence. Overnight, the Bloc leader became the de facto spokesperson for the ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ campaign.

For the federalist forces, what followed was a seismic shock. John Rae, a longtime Chr├®tien adviser, said that on his 50th birthday, 10 days before the vote, internal poll numbers came in that showed the ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ side in the lead. He recalled reporting the numbers around 10 p.m. that night to the prime minister, who calmly stated that theyŌĆÖd have to start working harder ŌĆö and they should all get some sleep.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It was certainly a flashpoint,ŌĆØ Rae said.┬Ā

In the dying days of October, the ŌĆ£noŌĆØ side pulled out all the stops. In cabinet meetings, Chr├®tien, who had weeks earlier warned his ministers not to appear overconfident, was now instructing them to keep their cool if Quebec voted to separate.┬Ā

"We were very concerned," said Eddie Goldenberg, Chr├®tien's senior policy adviser at the time. "I won't say it was panic, but it was, 'What the hell do we do now and who does what and how are we going to bring it back?'"┬Ā

Goldenberg recalled writing a last-minute speech for a televised address the prime minister gave on Oct. 25. ŌĆ£I kept saying to myself, ŌĆśWhat if IŌĆÖm giving him bad advice, and he takes it?ŌĆÖŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£What are the consequences? Because you can lose a country over that.ŌĆØ

Perhaps the most enduring image of the 1995 referendum is the hastily planned unity rally that drew tens of thousands of people from across the country to Montreal on Oct. 27.┬Ā

Then-deputy prime minister Sheila Copps, who helped organize the rally, accused the ŌĆ£noŌĆØ side led by the provincial Liberals of running an ŌĆ£absolutely horrible campaignŌĆØ that failed to appeal to QuebecersŌĆÖ hearts and tried to block involvement by the rest of Canada. She said people took hours-long trips to Montreal on school buses to attend the rally and show they believed in the country. "You can't beat that," she said. Her eight-year-old daughter was there with her.┬Ā

Harel remembers the rally in a different light. ŌĆ£It was a love that lasted as long as the life of a rose,ŌĆØ she said.┬Ā

Three days later, an astonishing 93.5 per cent of Quebecers turned out to vote. When the dust settled, the ŌĆ£noŌĆØ campaign had won 50.58 per cent of the vote, defeating the sovereigntist movement by fewer than 55,000 ballots.┬Ā

Beaudoin stayed in her riding office that night, as the reality set in. ŌĆ£It was the disappointment of my life in politics,ŌĆØ she said. Meanwhile, during his concession speech in Montreal, an angry Parizeau spoke the words for which he is probably best known, blaming the defeat on ŌĆ£money and ethnic votes.ŌĆØ

Bouchard struck a different chord in his own speech that night, urging sovereigntists to remain hopeful. ŌĆ£Next time will be the right time,ŌĆØ he said.┬Ā

Thirty years on, the legacy of the 1995 referendum is in the eye of the beholder. With the sting of defeat dulled by time, Beaudoin said she looks at the last referendum as one chapter of a book whose ending is not yet written. ŌĆ£These are steps in the life of a people,ŌĆØ she said.

St-Pierre Plamondon, who is pledging to complete the mission that L├®vesque began decades ago, said he has long thought of the referendum project as a trilogy. ŌĆ£I never thought that the first two referendums were failures,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£It is a cumulative process that will lead to truth and then to justice.ŌĆØ

Parisella, however, sees a different lesson in the moment when Quebec decided, just barely, to stay. ŌĆ£It shows that the system, as imperfect as it is, can work,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I remain confident that Canada will survive.ŌĆØ

This report by ║┌┴Ž│į╣Ž═° was first published Oct. 26, 2025.┬Ā

ŌĆō With files from Vicky Fragasso-Marquis